Being multiracial is about answering the question “Who are you?”, as Marcia Dawkins asked me when we met at a café in Israel. It was the first time I had ever been asked this question. I answered:

My instinct is to tell you what I am not, because I have always been fighting being defined. I’m not American. I’m not Israeli. I’m not Russian. I’m not black. I’m not a woman—as in I’m not defined by my status or sex. I’m not a mother, as in I’m not defined by this role. I am nothing; but not in the way of being unimportant. I just want to be. I’m just me. I’m Shoshana.

What I forgot to tell Marcia is that I don’t have the luxury of knowing who I am. When I mentioned these thoughts to my mother she said, “There’s something about U.S. society that makes you choose,” which are the remnants of the “one-drop rule” that refuses to die— a rule of Jim Crow segregation defining an individual with any known African ancestry as black, a form of hypodescent. Mom also told me I do not get to choose not to be black, exclaimed that I am American, and called this paragraph “poppycock!” when I read her my first draft. She has never been asked “What is your eda” (loosely translated as “ethnicity” in Hebrew) and not known the answer. I recently rediscovered a journal entry from 2007 where I wrote, “I have been told and told and told…who to be until I literally, actually don’t know who I am anymore.” Now, I know that because of who I am I don’t know who I am.

Perhaps Mom’s response is one reason why neither she nor I consider ourselves multiracial. My mother has curly hair, but I assume this is the result of history. All I know is that my great-great-grandmother was half Cherokee and half black and my great-great-grandfather was white. In America this ancestry does not allow me to define myself as multiracial. Why? Because my mixture is not immediate, and allegedly all black people in America have some Native American ancestry. My daughters are another story. One is multiracial and two are not. What is interesting is that one of my monoracial daughters is lighter than the mixed one. We bring these differences, these “what we are nots” to our blended family, though this is not where I take my credibility to discuss the subject. The fact that I even believe I need credibility is perhaps more of the issue. Though I have never considered myself multiracial, I have always felt as though I am. I have been taken for multiracial. I find myself drawn to multiracial people in the U.S. and in Israel, where I have lived for nearly half of my life. I even used to wish I were multiracial (at the time my preference was half-French) so that I would have another native tongue and an additional culture to enjoy. Perhaps this is because I share their way of being/ belonging nowhere and everywhere at the same time, of not being wholly of one culture.

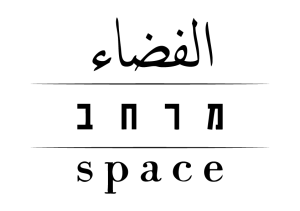

In Israel, mixed race is more complex than in America mainly because religion is, simultaneously, more important than race and is race, in the context of Judaism. The Ashkenazi (European Jews)/Mizrachi (Eastern Jews) discourse parallels the American black/white discourse culturally, but due to the shared religion/race of Judaism, multiracial identity in this context is much less poignant. Alternatively, the interaction between Jews of Ethiopian decent and those of European decent is slightly more riddled with discontent. This is due to the influence of American media, and the borrowing of language from the Civil Rights movement and race issues which leave stronger sentiments and scars of racism. Nevertheless, sharing Jewishness is a neutralizing factor. The real disquieting issue in multiracialism in Israel is mixing which crosses religious/racial boundaries—for instance, a Jew marrying a Muslim/Christian Arab or a Druze marrying a Jew.

The mere existence of an American living outside of the American context creates a multicultural experience. When there is an attempt to define an expatriate individual based on local identity categories, an even stronger parallel to the multiracial experience is created. This is the case when Israelis try to define me within a local context. Almost no American would mistake me for multiracial because I do not pass “the comb test” (a test of blackness based on hair texture; my hair would not easily concede to a comb). Because Israelis are not aware of the comb test, I am often assumed to be multiracial. In the Israeli context, there are the assumptions that (a) anyone not a tourist or a student who would come to live in Israel must be Jewish, (b) Ethiopian Jews are the only black Jews, and, therefore, (c) based on my complexion, I must be either a convert or half-Jewish. Aside from the assumption of my half-Jewishness, I am mistaken for various other mixed race combinations and nationalities—anything from Jamaican or Brazilian to Indian or French—which would not happen in America.

Just as in America as a child I was told I “acted white,” I am told in Israel that I fit into the Ashkenazi category because I am American. This is paramount to being told I “pass” into the “white” category, in terms of having an elevated social status. In other words, in Israel, I am culturally white!

Being an extensively acculturated resident of Israel for half of my life has blurred my identity. Sometimes I think in Hebrew, and despite not being Jewish, or even an Israeli citizen, I find myself and am found by Americans and Israelis alike to be culturally more Israeli than American, or experienced as just not American period. (My Egyptian American friend who works at the US Consulate threatens to revoke my US passport for lack of up-to-date American cultural innuendos.) When I was observant of a religious Jewish lifestyle, I was found by some secular Israelis to be “more Jewish” than they considered themselves.

Amongst Israelis, most of my friends in the country are from the former Soviet Union, including my Ukrainian Jewish husband. I have learned intermediate Russian (now Russian words pop into my head when I try to speak French), our kitchen is a mosaic of dishes from the Crimean Peninsula region, I wear a tryzub (the Ukrainian seal) necklace, and identify more with this segment of Israeli society than other groups, including Americans living in Israel, and especially African Americans living in Israel. My next largest category of friends in Israel is either mixed or “black sheep” (no pun intended) defined as not “fitting” into the cultural-racial group they were born into. These include friends who are Ukrainian Togolese (he calls himself a “Black Russian”), African American Israeli, Ukrainian American, Jewish Russian, Egyptian American, Ethiopian Israeli, and Palestinian American who “act white” as defined by their peers, and Russian Israelis who “pass” for native Israeli because they are “dark.”

I am reminded via social networking sites that I am disconnected from issues that concern many of my African American peers in the United States. This is clear in old debates such as the “Why is it hard to find a good black man?”; I tend to be the only voice saying, “Why not look for a good man, period?” Or during discussions of the Trayvon Martin tragedy where I was the only one of my black Facebook friends who did not dedicate a status update to the case. “Honestly,” I responded to another friend’s status, “because I believe it’s a human issue and I don’t normally toot my horn about most of what I find appalling news in this world I hadn’t planned on addressing it at all.” I have felt estranged from blackness, yet simultaneously suffered from it since childhood, mainly from my strongest black feature, my hair.

My identification with the multiracial experience began in childhood as a multicultural individual within the American black/white context. In the United States, the story is so old it feels redundant to even give a small review. There was slavery, there was Jim Crow, there were “Our Kind of People,” there was the Civil Rights Movement, there was desegregation, and there was “re-segregation” (the repolarization of black and white communities and schools), and this is where I come in. My earliest school memories, in an elementary school in Brewton, Alabama, in a relatively racially mixed school, were of the boy who made fun of my “BB buckshots” and the “pots and pans in my kitchen.” These were references to the texture of my hair. This boy was black. I also remember being told that I “spoke white.” Speaking white is a term referred to one speaking grammatically correct English as opposed to African American vernacular English. I ended up having mostly white friends because my black classmates told me that I was not black. To this day, I am still not 100% sure what that means. I just did not fit in culturally. I suffered no such self-consciousness with my white classmates, and this was Alabama. To be fair, during my summers in Buffalo, NY, my cousins told me I “sounded country” so maybe I had accent issues.

Fast forward to high school in Baltimore, MD, in the 1990s. This was a predominately black school and I still “wasn’t black” enough. I was told I didn’t have rhythm and teased for the unfashionable hairstyles with the nappy hair clearly not straightened properly in the back. Though I’d started off closed-minded mainly due to the ignorance of my inexperience, I began listening more to alternative music, defined by my classmates as “white music,” and less to “black music” like the R&B and rap popular amongst my peers. I was called out for that as well. It was once said of me: “Shoshana doesn’t drink Kool-Aid, she drinks Perrier. She doesn’t eat Oodles of Noodles, she eats Fettuccine Alfredo.” Guilty as charged. So, I was very empathetic when a foreign-educated mixed friend, said “They say I’m not black until they see that I’m smart and then they say, ‘She’s a smart black person.’ Why don’t they make up their minds?” On one hand, she was rejected as “not black” culturally; on the other, blacks wanted to claim her achievements in the name of black prestige. It is but one example of the limbo suffered by the multiracial and multicultural alike.

I am not multiracial, but I was never allowed to feel black enough either. Strangely, when I went natural with my hair and started my locks in 11th grade, I became “too black” or at least too nappy for some. I was called a wannabe Erykah Badu, as Afrocentricism was becoming the new style on the fringes of high school society. But I did not change my hair because I was becoming Afrocentric. I did it because one day while returning from a band trip (I’d found the courage to dance as a flag girl with the marching band— turns out I had rhythm after all), I suddenly remembered that boy from elementary school who made fun of my “buckshots” and realized that I hadn’t permed my hair because I thought it was more beautiful; I did it because I had been teased. I decided to break free, and I have loved my hair ever since despite the loaded message it sometimes sends to others. I have locks simply because they are beautiful and easy—no, I don’t like reggae music. Really.

These experiences with my family, peers, and hair, combined with my indefinite relocation to Israel, contributed to the weakening of my black/African American identity and the strengthening of my “refusing definition/multicultural/citizen of the world” identity. In the United States, historically, multiracial identity—usually biracial identity—has meant having to choose sides: Either pass for white according to the paper bag and comb test or be black according to the one-drop rule. Currently, multiracial identity in America seems to mean simultaneously belonging to two or more groups and yet really belonging to none. It is a debate of being defined and about rejecting definition. Yet, just as race in itself is a social/cultural construct, so are these definitions and the sense of belonging that accompanies them. It’s less about belonging to a color than belonging to a culture. Paradoxically, as much as I oppose this discourse insisting on defining me, I am caught in it. I have been defining myself as not multiracial when I, very literally, am. We African Americans are multiracial, but we weren’t allowed to be multiracial. Why are we still following the one-drop rule? And why are blacks victimizing other blacks concerning their blackness, knowing we are all mixed anyway? Why? Because someone in history said that I don’t get to choose. Well, I say that I do. I can choose not to choose. According to Cassar (2008), “the identity is not several but one, made up of all the elements (which we could call tesserae) that have shaped and continue to shape it” (p. 19). Perhaps this is why I love making collages—I am one.

The core of multiracial identity is blurring identities: simultaneously belonging to multiple categories and yet belonging exclusively to none. Multicultural people share a blurring of identities in a way very similar to those born multiracial, which is why in today’s global village, multicultural may be considered as the new multiracial. Multicultural individuals are loosely defined including, but not restricted to, those who are extensively acculturated expatriates and immigrants; partners in interracial relationships or parents of multiracial children; converts, particularly to Judaism where the lines between religion and race are blurred; individuals whose physical appearance causes them to be mistaken for multiracial or of the “wrong race”; individuals who define themselves as citizens of the world or even individuals who, for whatever reason, do not fit comfortably into the social/cultural/racial category they were born into but mesh well across other social/cultural/racial categories and carry an elusive sense of belonging nowhere and everywhere simultaneously.

This is not an essay about how I am not black or not American. It is about insisting upon the self-determination of my identity and hopefully giving others permission to do the same. In fact, perhaps in all that I have said, I make a stronger claim on my Americanness, for Harper and Walton (2000) have found that “to be ‘American’ is to be in constant search of one’s identity” (p. xxiv). Yet this still makes me cringe, and I get angry when people tell me to “come home.” I am still figuring this out. I embrace my American blackness in dance, jazz, and especially poetry, since I am a poet—these are a few of the many tesserae that I am composed of. Hughes (1995) once declared, “A poet is a human being. Each human being must live within his time, with and for his people, and within the boundaries of his country” (p. 5). But what is my country? Who are my people? Am I of my times? Perhaps telling me to come home is upsetting because I am not American, but I am; I am not Israeli, but I am; I am not black, but I am. It’s not about coordinates. It’s that everywhere I find mosaic people like me, I am home, in my country, with my people…and I defend my nomadic homeland of the heart fiercely.

References

Cassar, A. (2008). Muzajk: An Exploration in Multilingual Verse. Valletta, Malta: Edizzjoni

Skarta.

Harper, M. S., and Walton, A. (Eds.). (2000). The Vintage Book of African-American

Poetry. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Hughes, L. (1994). Introduction. In A. Rampersad and D. Roessel (Eds.), The Collected Poems

of Langston Hughes (pp. 3-7). New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Originally published: “Multicultural as the New Multiracial,” Mixed Race 3.0: Risk and Reward in the Digital Age, 2015

Check out the entire Kindle book on Amazon!